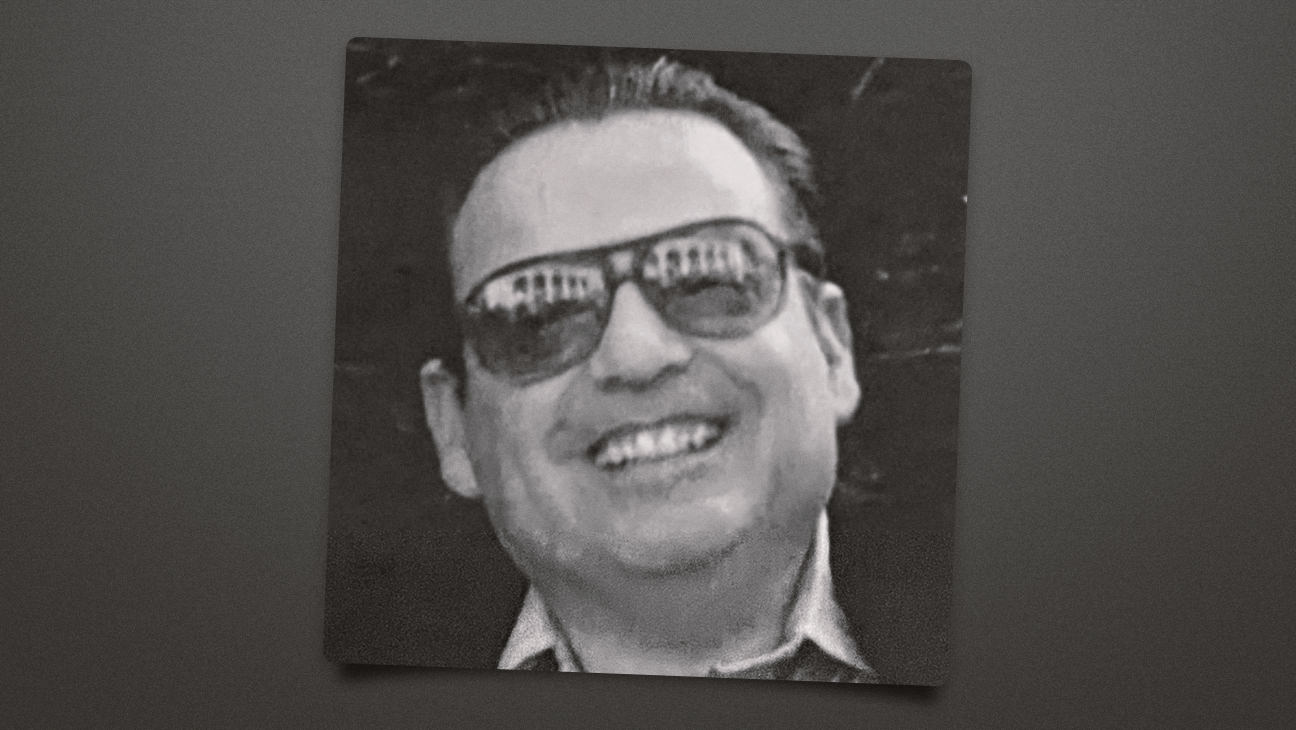

Pioneering Hollywood movie marketing strategist Allan Freeman has died. He was 88.

Freeman died on June 7 due to unspecified causes, former friend and colleague Martin Lewis, a movie and music marketing strategist who worked as a consultant with Freeman on United Artists projects, told The Hollywood Reporter. Sid Ganis, a former president of Paramount, chairman of Columbia, Lucasfilm exec and president of the Motion Picture Academy, in a statement praised his former colleague and friend.

“Allan Freeman was a pioneer. Someone had to invent research for movies and Allan was the one!” Ganis said. Freeman, who worked behind the Hollywood curtain on film releases for Superman, Star Wars and Rain Man, as an early research director at Warner Bros. introduced film title testing and research strategies to ensure a tentpole release better hit with audiences in theaters by avoiding pre-release confusion about a film’s plot or characters.

“The reason we test all our titles is that if the title does present a communications problem, we’d like to know what it is even if we don’t intend to change it. We need to know what to do with our advertising to counteract it,” Freeman said in a Dec. 24, 1978 New York Times story. The principles of Madison Avenue and political polling that Freeman brought to Hollywood in the 1970s informed many of the movie industry’s promotional strategies for years to come.

He got behind iconic marketing campaigns for Dances with Wolves, The Silence of the Lambs, The Shining and Splash to determine how a film’s title, trailer and poster may play with audiences, much as marketers had already used data research to sell soap or toothpaste.

Freeman’s goal was to transform a Hollywood where top studio execs for decades had used little more than hunches about what audiences may like into an industry where market research and numbers replaced gut instinct and guesswork.

Freeman began his career producing advertising campaigns for major marketers like General Foods and Bristol-Myers. In the early 1970s, he moved from pharmaceuticals to film by working for Palomar Pictures, a production unit acquired by Bristol-Myers.

Freeman launched his own boutique consultancy to craft campaigns for Sleuth (1972), The Heartbreak Kid (1972), The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) and The Stepford Wives (1975).

His movie promotion techniques gained the attention of Twentieth Century Fox, where studio chairman Dennis Stanfill and president Alan Ladd Jr. in 1975 hired Freeman as a consultant and eventually as their in-house vice president of market research.

At Fox, Freeman launched campaigns for several hit films including The Omen (1976), Silent Movie (1976), Star Wars (1977) and the Oscar winner Julia (1977). With The Omen, Freeman helped reposition a low-budget horror film into a box office winner by changing one of the movie’s original titles, Birthmark.

“The ideal title should be compelling in its own right. For example, The Omen tested as scary, ominous and yet a quality film. The ideal title should position the film properly in a person’s mind so that you don’t have to spend half your TV and print advertising explaining what it means. For example, Sorcerer had nothing to do with the film and made it sound like a supernatural picture, which it wasn’t. Finally, the ideal title should itself be a form of advertising — it should start communicating a right message,” Freeman said in the 1978 New York Times article.

Warner Bros. vice chairman Frank Wells then brought Freeman to work at that major studio. There he partnered with another marketing guru, Andrew Fogelson, father of current Lionsgate Motion Picture Group chairman Adam Fogelson. Fogelson, who served as president of marketing for several studios, including Warner Bros., Columbia and United Artists, credited Freeman with revolutionizing the way Hollywood marketed films.

“Allan arrived in the motion picture marketing business at a time when ‘conventional’ marketing hadn’t yet met movies. I met him and found him to be astonishingly bright, business-like and convinced we could learn a lot from the rest of the business world. While my superiors (let’s call them ‘bosses’) were highly dubious, they stepped aside and let us experiment. In short order his efforts on Superman, Oh God and The Goodbye Girl were demonstrably and hugely helpful. ‘Dubious’ left the scene, to be replaced by studios calling to see if they could buy into the new system that was being created,” Fogelson said in his own statement.

“Today it’s a multi-million-dollar business, in which — in one way or another — everyone participates. And we owe it all to the wit and wisdom of Mr. Freeman. God bless,” Fogelson added.

Among other research-driven promotional campaigns Freeman got behind were for Clint Eastwood’s Every Which Way But Loose, Burt Reynolds’ Hooper, Capricorn One (which launched a long collaboration with director Peter Hyams) Monty Python’s Life of Brian and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.

In 1980, Freeman reactivated his boutique agency and over the next seven years helped market Inside Moves for Richard Donner, First Blood, This is Spinal Tap, Tron, Never Cry Wolf and Splash.

His association with Disney reunited him with Frank Wells who became the studio’s president. In 1985, Freeman, on the promotional launch for The Emerald Forest, made use of extensive telephone interviews with focus group members to help refine the film’s narrative and flow.

That use of focus group testing earned criticism that studio execs were abdicating their creative responsibilities when making and releasing movies, but Freeman maintained hard data was crucial to reassuring the major studios and reaching cinema audiences.

In 1987, Fogelson brought Freeman into United Artists as a senior marketing executive, where he got behind major releases for The Living Daylights (1987), Baby Boom (1987), Overboard (1987), Child’s Play (1988), I’m Gonna Git You Sucka (1988), Rain Man (1988) and Road House (1989).

For Rain Man, Freeman purposefully teased the film without giving away major plot points during pre-release advertising. “We’re not trying to confuse anybody and not trying to mislead anybody. But to tell you the whole story in the ads takes away the actual charm of making it unfold before you in the theaters,” Freeman told a Dec. 9, 1988 Los Angeles Times story.

“He was incredibly insightful as to what worked and what didn’t work. There were a few copycats in the industry offering a similar technique. But having devised the paradigm of research-driven creativity nobody did it better than Allan. He inspired his staff and outside consultants to aim higher and be more daring. If you created something good — he praised you. If you went off the rails (as I occasionally did) he reined you in sharply but with dry humor. I learned a lot from Allan. He thought outside-the-box. He was an original. He stuck out like a healthy thumb,” Lewis, whose promotional campaigns include those for The King’s Speech, Crash, The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball and a host of Beatles and Monty Python projects, said in a statement.

After leaving United Artists, Freeman turned to indie movies, and helped market Oscar best picture winners Dances with Wolves in 1990 and The Silence of the Lambs a year later.

Freeman is survived by his wife Barbara and his children Joanne, Richard and Marc.

#Allan #Freeman #Dead #Pioneering #Movie #Marketing #Strategist